|

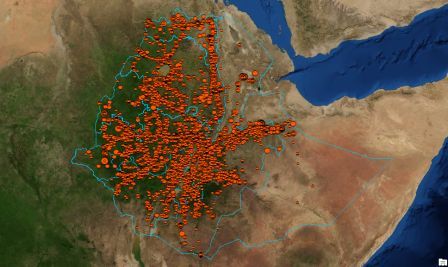

| This map, made with GIS, shows the frequency of DKT Ethiopia sales contacts in 2012. |

NOTE: This originally appeared in the Huffington Post on April 24, 2013.

ADDIS Ababa, Ethiopia -- In just six years, DKT Ethiopia has transformed its system for tracking contraceptive sales from pins and pencils to computers and satellites and, in the process, helped create a family planning and HIV prevention success story in the Horn of Africa.

DKT Ethiopia is an affiliate of DKT International, a non-profit organization that seeks to provide couples with affordable and safe options for family planning and HIV prevention in 19 low- and middle-income countries. In Ethiopia, DKT uses social marketing to distribute three brands of condoms (and eight variants), three oral contraceptive pills, two IUDS, two injectables, one brand of emergency contraception and several other health products.

It was in 2007 that DKT Ethiopia started using GIS (Geographic Information System), a tool to display and analyze sales, finance and inventory information geographically and, particularly, to plot every one of its 30,000+ direct and indirect sales outlets. This has made an enormous difference in DKT's ability to know how its contraceptive sales are going in every corner of Ethiopia.

Before 2007, DKT used pins, pencils and Excel spread sheets to track this information, making it difficult and sometimes impossible to produce the desired information.